According to a recent rat study by scientists at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, a tumor’s necrotic core includes elements that seem to encourage metastasis or the dispersal of tumor cells throughout the body.

The week of February 27 will see the publication of the research results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Researchers hope that this will help people understand how to treat metastatic cancers, also known as stage 4 cancers, which are treatable but incurable.

Ami Yamamoto, the lead author and a graduate student at Fred Hutch working in the Cheung Lab, said that although tumor necrotic cores are a fairly typical occurrence, they haven’t previously been connected to cancer metastasis. “Our study combined prior findings into the particular context of breast cancer metastasis. According to our research, necrosis, circulating tumor cells, and cancer spread are all related.”

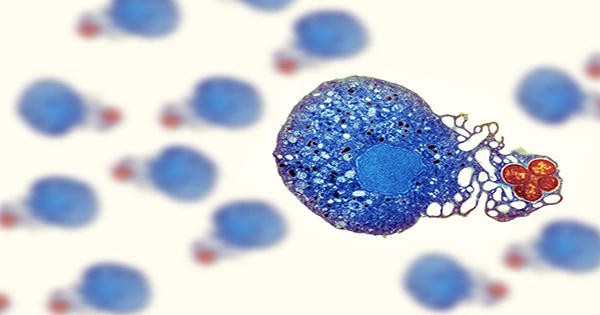

What is a dead zone

Necrotic cores, which are masses that are perishing from the inside out, provide the ideal conditions for the spread of cancer.

According to Yamamoto, dead zones of tumors have leaky blood vessels, hypoxia, or low oxygen levels, and the recruitment of immune cells, some of which have been demonstrated to assist in the spread of cancer cells. “What we believe is going on is that the necrotic core is mostly a dead zone, but it also has some surviving tumor cells that help the disease spread in the body,” the researcher explained.

In their field of work, surgeons, pathologists, radiologists, clinicians, and researchers frequently encounter necrotic cores, which are typically not a positive sign.

“Necrosis is a clinical finding seen in aggressive tumors that grow rapidly,” said lead author Kevin Cheung, MD, a physician-researcher at Fred Hutch. “When we see it in a biopsy of a patient, it indicates this is a dangerous tumor that needs to be treated quickly,” the doctor said.

However, necrosis is not only a feature of big, late-stage tumors, according to Cheung. Small and early-stage cancers are also susceptible to it.

A protein linked to necrosis and cancer spread

To investigate the necrotic core of tumors, the Fred Hutch team created a new rat model of breast cancer metastasis. Yamamoto monitored the development of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), a marker of whether cancer cells are making their way into the bloodstream to disseminate throughout the body, over the course of several weeks. At the first two time points they looked at (after 13 and 17 days), they discovered no CTCs; however, by the fourth time point at 27 days, they had discovered some.

Immediately, hundreds of CTCs were discovered, according to Yamamoto. She connected the development of a sizable central region of necrosis in the primary tumor with the rise in cancer cells.

An in-depth analysis revealed a striking variation in gene expression between the necrotic and non-necrotic tumor regions.

“We discovered that the most enriched tumor-derived gene in the necrotic and areas adjacent to necrotic regions of the tumor was a gene that encodes angiopoietin-like 7, a secreted protein,” Yamamoto said.

Angiopoietin-like-7, a single protein, was discovered to modify the tumor microenvironment, urging the tumor cells to outgrow their nutrient capacity, enter necrosis, and begin spreading to other regions of the body.

This was unexpected, Cheung remarked. “We believed that necrosis was completely uncontrolled and uncontrollable.”

Then Yamamoto conducted tests to determine how altering the protein would affect necrotic.

“There was a dramatic decrease of necrotic tumor area when we suppressed the expression of this protein in the tumors,” Yamamoto said. Angiopoietin-like 7 (A-7) suppression also significantly decreased distant metastases, dilated, large blood vessels, and circulating tumor cells to almost negative levels.

A-7 regulates not only the growth of central necrosis in the primary tumor, according to Yamamoto’s study, but also the growth of dilated blood vessels, which may aid in the metastasis and spread of circulating tumor cells.

A potential new target for treatment

These results revealed the potential for a brand-new, patient-specific treatment, which went beyond the surprise of such a significant mechanism for necrosis.

Our final objective, according to the researcher, is to create a therapeutic antibody against A-7 that will stop or lessen metastasis in patients with metastatic breast cancer.

To that end, the team has already identified more than 200 potential anti-A-7 antibody candidates, but they still need to screen each one to determine which ones effectively inhibit the function. To better comprehend the relationship between tumor necrosis and the risk of metastatic dissemination, Cheung said he and his team also plan to examine the data from sizable patient cohorts.

“Some people have blood that shows markers of necrosis,” he said. That could mean that people as well as preclinical models are experiencing this.

Cheung and Yamamoto also wish to explore the remaining issues.

We probably thought the necrotic core was the least intriguing part of the tumor before we began this, according to Cheung. “We are now certain that the interior is a really fascinating location to investigate the origin of spread cancer. There is still more cancer biochemistry to be discovered.”

Source: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2023-02-dead-zone-tumor-cancer-protein.html