When we presume that spaces and objects on a flat surface (such as a picture or a television screen) have depth, we are adopting a series of visual cues that provide the impression that the space is three dimensional. Today, 3D cues are so prevalent that we hardly even notice them. These signals were not always utilized and comprehended, and in some preliterate communities today, people may still find it challenging to comprehend 3D illusions. The development of our spatial thinking skills depends on our capacity to comprehend how these illusions operate. When navigating unfamiliar streets, figuring out how to wrap fabric around a body to create a certain fashion idea, visualizing the inner workings of a complicated system or body component, or even accurately sketching what we see, spatial concepts come into play.

The Romans of antiquity were adept at capturing depth in their paintings. European artists, however, lost their ability to effectively depict three-dimensional illusions during the Middle Ages. In fact, in the early Christian era, persons and landscapes were intended to serve as a type of generic shorthand for the religious and historical events being communicated, thus this level of realism was not required for the goals of visual imagery. Realistic representations of the physical world were not desired; rather, stylised images of historical and religious themes were preferred, which could be readily recognized by a devoted but uneducated populace. Due to this, medieval artwork like this one typically appeared flat or sent contradictory messages about the three-dimensional space being portrayed.

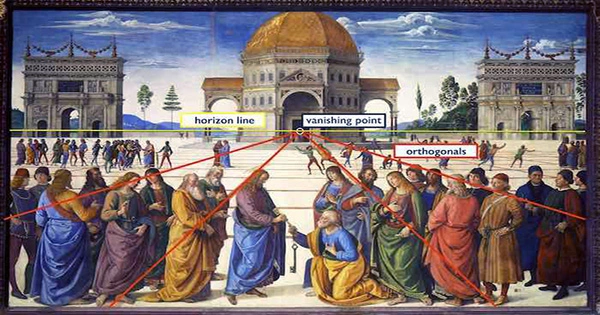

This all changed in the late 15th century when designers and painters realized the importance and influence of three-dimensional effects in drawings and paintings. This complemented the period’s intellectual pursuits, which valued truth, realism, and uniqueness. Paintings were transformed into a sort of mystical portal into a highly believable world thanks to three-dimensional effects, which were hailed as a fantastic, almost magical illusion. The dramatic instances of the Renaissance’s obsession with this new toolkit are Raphael’s paintings. Visit this website and select Early history of perspective for further details on the development of linear perspective.

We have all spent our entire lives observing two-dimensional representations of what appears to be three-dimensional space. The visual techniques that are employed to create this illusion are taken for granted by us. However, even now, such visuals are difficult to grasp or comprehend in some isolated societies. Overlapping, shifting size and position, linear perspective, relative hue and value, and atmospheric perspective are techniques for producing the illusion of three-dimensional space.

Overlapping is the most basic tool for depicting three-dimensional space. Allowing one form’s contour to be broken by another’s, causing one to take precedence over the other, produces the desired result. In this Byzantine mosaic, one object serves as the lone spatial cue. The sole slight cue that identifies who is in front and who further behind comes from the overlapping of clothing, giving the whole composition the appearance of being fairly flat. It gives the impression that everyone is pressed up against the picture’s “window,” which is a rather flat impression.

By altering size and positioning, spatial cues are supplied at a higher level. Prior to the addition of shifting size, placement alone was used, but to modern eyes, the illusion was not entirely believable.

The development of linear perspective in the 15th century was the biggest advancement in the visualization of three-dimensional space. The illusion that objects appear to get smaller and move toward a “vanishing point” at the horizon is known as linear perspective. The horizon/vanishing point may be real or imagined, and the point of convergence may be anywhere the viewer sees, including up. Linear perspective depends on paying attention to how items’ forms relate to where they are placed.

Mathematically predicted, the rate at which shapes appear to change in size and location is regular. To imply perspective, the form (such as a cube) must also be deformed. A surprising new level of realism in drawing was also enabled by these mathematical advancements, which became the major passion of Renaissance artists. In turn, new spatial effects in architecture were developed as a result of the illusions of linear perspective in drawing. You can visit to see an example of linear perspective in action, or click this link for an interactive version.

Value and hue are crucial indicators of an object’s distance from us. Warm colors are typically viewed as being closer than cool colors. Colors that have a great difference in value appear to split in space, whereas colors that are near in value appear to be close to one another in space. Distant objects typically have desaturated hues and identical or neutral values. Close objects often have more intense, vivid colors and/or sharper contrasts between light and dark values. The trees and sky beyond the lake are undoubtedly comparable in color, but they appear to be more neutral in value and desaturated in hue, with less contrast, in this environment. The largest hue and value contrasts, however, occur where the trees overlap the lake. Furthermore, the warmer hues of the foreground leaves push the image forward, whereas the cooler hues of the distant coastline and the sky tend to pull the image back.

The above characteristics are combined in atmospheric viewpoint. It works when things that are supposed to be far away but are put in the upper part of the page lack contrast, detail, and texture. The upper third of the page in this Hieronymus Bosch artwork often has less contrast and detail. In addition to the fact that distant objects typically appear in the upper half of your field of vision, distant objects will not be extremely brilliant or light in value, nor will they be brightly colored (intense in hue). Contrarily, the lower half of the picture plane is more likely to have detail, texture, and hue and value contrast, as they do in this instance.

These traits are combined, as in this artwork, to great effect. The three-dimensional illusion is disrupted if any of these ideas are disregarded or purposefully put at odds with one another. To provide the appearance of immense distance, this image uses overlapping, relative size and placement, linear perspective, color, value, and atmospheric perspective. All of these guidelines can be deliberately broken in order to produce three-dimensional illusions that deceive the observer and/or are impossible to realize in a three-dimensional model.

(Not only do some of the graphics in this linked site relate to spatial principles, but also to color concepts that we shall cover later.) However, the guidelines used to create perspective in Chinese art are only different. Often referred to as “floating perspective,” this method alters the point of view of the linear perspective as the spectator moves from “near” to “far” areas of the image (see this example of floating perspective in Chinese landscape painting).

The foundation of architecture and the majority of designed products is three-dimensional shape and space. There are additional design considerations because the thing will be seen from multiple angles. Since the final use primarily concerns the space that will be inhabited, the shape’s design in architecture is practically secondary to the design of the space it contains. The area that the sculpture’s shape defines may be crucial to the overall design of sculpture as well.

The function of other designed things, such as furniture, tools, and appliances, as well as frequently the features of the human body that will utilize the object, must be considered. The challenge for fashion designers is to convert a two-dimensional substance (cloth) into a three-dimensional form (a body-shaped garment), which is a particularly challenging and intricate topographical engineering problem.

Like line, three-dimensional shape has an expressive language. Given that shape’s contours always imply line, this makes sense. For instance, rectilinear shapes imply steadiness. Instability is suggested by angular structures positioned diagonally with respect to gravity. Softly curved surfaces in shapes imply peace, comfort, and sensuality.