Autotrophs are producers that grow their own food in the ocean to provide energy. Ocean consumers often referred to as heterotrophs, eat producers to obtain the energy they need to exist.

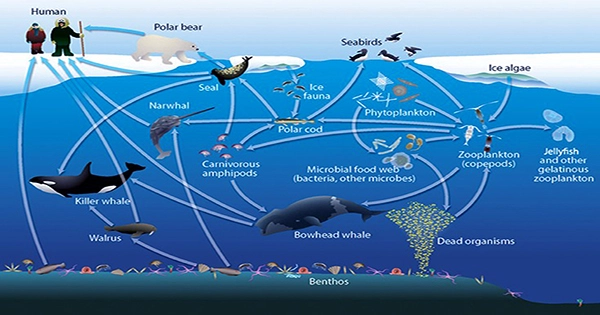

Food chains on land and in water show how caloric energy moves in a straight line from producers to consumers at various trophic levels. But in reality, consumers have a variety of providers to pick from in every ecological system. Additionally, some consumers eat both plants and animals since they are omnivores. Furthermore, certain carnivores (creatures that consume flesh) feed on animals of all sizes. Therefore, regardless of the type of community, food webs show the true essence of how all creatures interact with one another. The ecological community’s web of life could begin to fall apart if one creature disappears, which would drastically alter how that ecological community endures in the future.

For instance, if there were no polar bears to feed on ringed seals, the number of ringed seals might expand to a point where it significantly outnumbers Arctic cod populations. With fewer cod in the ocean, zooplankton and other crustacean populations (like krill) may grow, further upsetting the biological balance of the ocean.

Regardless of the temperature of the sea, biologists can locate them wherever in the world. However, warmer ocean temperatures are home to the greatest variety of marine producers (and their consumers). Ectotherms, such as fish and invertebrates, rely on the temperature of their surroundings to keep their bodies at a constant temperature. In order to support mobility and food metabolism, organisms that live in icy seas, such as those close to the North and South Poles, must have special strategies to stay warm. Endotherms like whales and sea lions use blubber to insulate their body tissue and keep their body temperature stable.

Polar bears, which have thick fur coverings of fat layers, and penguins, which have water-repelling feathers covering downy, heat-trapping feathers, are examples of additional endotherms. But in order to prevent their bodies from freezing, ectotherm fish must rely on particular glycoproteins found only in a small number of fish species. Ocean habitat type is a significant contributor to marine biodiversity in addition to ocean temperature. Estuaries (where rivers meet the ocean) and mangrove forests, as well as coral reefs and rocky and sandy coastal coastlines, are teeming with producers and consumers. Where the ocean floor is shallow enough to absorb sunlight, these marine ecosystems can be found close to land.

Like on land, ocean ecosystem producers use photosynthesis to create glucose, a sugar molecule, and oxygen by absorbing sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. Sunlight filters through the water where the ocean is relatively shallow to aid the growth and reproduction of photosynthetic creatures such as phytoplankton, seaweed (a form of algae), kelp, and seagrass. Oceans have enough of dissolved carbon dioxide to assist primary producers’ photosynthesis as a sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Surprisingly, 95% of the energy produced in the world’s oceans is due to various forms of microscopic phytoplankton. Additionally, they produce at least 50% of the oxygen present in the atmosphere of the planet. Diatoms and dinoflagellates are two types of phytoplankton that are bacteria and protists that resemble plants.

Another method of glucose synthesis takes place, this time by chemical reactions as methane seeps and hydrothermal vents release hydrogen sulfide. The bacteria that live on the sandy floor’s substratum can produce glucose from the methane and hydrogen sulfide that are stored in seeps and vents, respectively. The diverse range of life is supported by chemosynthesis, the creation of inorganic molecules. Even some other marine species, such as giant tube worms and mussels, serve as hosts for the chemosynthetic bacteria, allowing the entire process to take place inside their digestive systems.